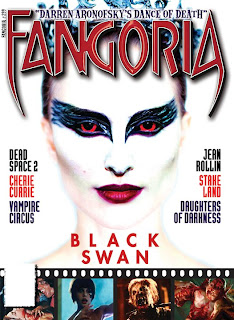

Since my entry into the FANGORIA staff in late August, I've been nothing short of ecstatic to be covering the beat of the melding of class and trash, sleaze and beauty more formally known as the horror genre. FANGORIA #299 is now on shelves, with a cover story dedicated to Darren Aronofsky's "Black Swan." The magazine has been making some incredible strides and interesting revamps, some completely fresh and others returning back to cherished and seemingly (though only temporarily) lost roots.

In addition to an in-depth look at Aronofsky's psycho-thriller, horror fiends will also find set coverage of Jim Mickle's "Stake Land," a nice look at Sage Stallone (son of Sylvester)'s adamant revival of Grindhouse Releasing, an interview with French auteur Jean Rollin, and can find my review of the recent Aussie creature feature "The Dark Lurking" at Dr. Cyclops' Dungeon of Discs.

Wednesday, December 8, 2010

"Black Swan" (2010)

Darren Aronofsky's "Black Swan"never once reveals exactly what it is, which is ironic. The film's wildly unrestrained psychosomatic narrative is devoted to subjectivity, free to romp in artistic grandeur, though it's crafted around one calculating, rigidly disciplined performer who can't allow her mind to be free for a second. The young woman is Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), and her passion and elegance is apparent as we observe her daily routine - her walk from the humble apartment she shares with her loving, if not coddling mother (Barbara Hershey) to her New York City ballet company, run by one formidable director Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassell). It is here where Nina will thrash out the limbering precision of her dance regiments, in preparing for the company's production of Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake, for which swarms of students covet the lead of Swan Queen. Leroy acknowledges that the ballet has been done ad nauseam, but this time it's going to be "stripped down, raw, visceral;" "Black Swan" brilliantly encompasses the concise leanness of Leroy's approach along with its sinister facets that lie beneath.

It is nominally a hybrid adaptation of Dostoyevsky's novella The Double and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1948 balletic opus The Red Shoes, yes, and how paranoia and competition can dwindle away at the most committed of minds under the portent of pressure. But just as Rosemary's Baby - a seminal film for Aronofsky which the director publicly cites to be of major influence - was less concerned with the occult than with the perils of invested trust, so too is "Black Swan" devoted to greater thematic layering. It is a fascinating portrait of obsession, a film that sees the disturbing hum of anxiety in the physical manifest - thus the players in this gorgeously twisted world become slaves to the life-long audition from which they cannot escape.

A cunning balance of seduction and sweetness with unsettling repulsion, "Black Swan" works effectively as dynamic melodrama before taking a wicked turn into Cronenbergian horror-fantasy. Natalie Portman anchors this expertly as the fragile, innocent young talent navigating her way down the darkest corridors of sexuality and the looming threat of failure. Nina is suffocated by the expectations of all those around her to embody both the White and Black Swan - the former being her perfect match, the latter evading her grasp. That she is challenged for the dual role by the presence of a more naturally "free" Lily (Mila Kunis) only accelerates the rapid pace of her fears, which soon begin to surface skin deep.

Empathy for Nina might have been hard to find in a world this insular, but Portman's fearless performance along with the same knack for minutia and realist grit of Aronofsky's 2008 The Wrestler allow the material to transcend in a lavish romp that begs us to surrender to its dazzling visual splendor. Hand in hand with Aronofsky's apt study of the athleticism of the human body, we observe Nina's identity slowly begin to rear its freakish, other-worldly head - only to snap back with lightning speed to the hallucinatory discovery of her bodily desires.

Two minor female roles - Hershey as Erica Sayers and Winona Ryder as womanizing Leroy's former "little princess" Beth Macintyre - cleverly craft the picture's lingering tales of the original story's traditional "dying swan" element without relying too heavily on overt plot points. Both women, in their jealousy and obsession to live vicariously through the ballet that offers Nina the ideal career, underscore the political tensions that come along with any modern backdrop of competition. Erica listens and supports, but pushes and antagonizes once too far, while Beth's long-gone days as Swan Queen remain all too foreboding of Nina's hellish descent into madness.

As we check in and out, along with Nina's mind, to the internal, hushed sounds of buzzing audiences, the picture lulls deeper into absurdity, and by the third act the film asks us to check all rationale at the door. Though in this case, the sensationalist flair with which Aronofsky crafts "Black Swan"'s final choreography sequences (gorgeously staged by Benjamin Millepied) along with frequent collaborator Clint Mansell's masterful arrangement of Tchaikovsky's original score make the stunning rite of passage all the more poignant, never bordering on potential camp territory.

"Black Swan"'s ability to polarize audiences will ultimately lie in how its maker's utter disregard for restraint or conventional form will sit with those on the receiving end. It is a film that refuses to sit still and commit to certainty, but in this case that's hardly a criticism. The tragedy of Nina's blind ambition will remind the film's lovers and detractors that perfection, if it can be reached at all, cannot be reached without a leap of faith.

★★★★★ (5/5)

Cast & Credits

Nina Sayers/The White Swan: Natalie Portman

Lily/The Black Swan: Mila Kunis

Thomas Leroy/The Gentleman: Vincent Cassel

Erica Sayers/The Queen: Barbara Hershey

Beth Macintyre/The Dying Swan: Winona Ryder

Fox Searchlight presents a film directed by Darren Aronofsky. Written by Mark Heyman, Andrew Heinz and John McLaughlin. Running time: 108 minutes. Rated R (for strong sexual content, disturbing violent images, language and some drug use).

It is nominally a hybrid adaptation of Dostoyevsky's novella The Double and Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1948 balletic opus The Red Shoes, yes, and how paranoia and competition can dwindle away at the most committed of minds under the portent of pressure. But just as Rosemary's Baby - a seminal film for Aronofsky which the director publicly cites to be of major influence - was less concerned with the occult than with the perils of invested trust, so too is "Black Swan" devoted to greater thematic layering. It is a fascinating portrait of obsession, a film that sees the disturbing hum of anxiety in the physical manifest - thus the players in this gorgeously twisted world become slaves to the life-long audition from which they cannot escape.

A cunning balance of seduction and sweetness with unsettling repulsion, "Black Swan" works effectively as dynamic melodrama before taking a wicked turn into Cronenbergian horror-fantasy. Natalie Portman anchors this expertly as the fragile, innocent young talent navigating her way down the darkest corridors of sexuality and the looming threat of failure. Nina is suffocated by the expectations of all those around her to embody both the White and Black Swan - the former being her perfect match, the latter evading her grasp. That she is challenged for the dual role by the presence of a more naturally "free" Lily (Mila Kunis) only accelerates the rapid pace of her fears, which soon begin to surface skin deep.

Empathy for Nina might have been hard to find in a world this insular, but Portman's fearless performance along with the same knack for minutia and realist grit of Aronofsky's 2008 The Wrestler allow the material to transcend in a lavish romp that begs us to surrender to its dazzling visual splendor. Hand in hand with Aronofsky's apt study of the athleticism of the human body, we observe Nina's identity slowly begin to rear its freakish, other-worldly head - only to snap back with lightning speed to the hallucinatory discovery of her bodily desires.

As we check in and out, along with Nina's mind, to the internal, hushed sounds of buzzing audiences, the picture lulls deeper into absurdity, and by the third act the film asks us to check all rationale at the door. Though in this case, the sensationalist flair with which Aronofsky crafts "Black Swan"'s final choreography sequences (gorgeously staged by Benjamin Millepied) along with frequent collaborator Clint Mansell's masterful arrangement of Tchaikovsky's original score make the stunning rite of passage all the more poignant, never bordering on potential camp territory.

"Black Swan"'s ability to polarize audiences will ultimately lie in how its maker's utter disregard for restraint or conventional form will sit with those on the receiving end. It is a film that refuses to sit still and commit to certainty, but in this case that's hardly a criticism. The tragedy of Nina's blind ambition will remind the film's lovers and detractors that perfection, if it can be reached at all, cannot be reached without a leap of faith.

★★★★★ (5/5)

Cast & Credits

Nina Sayers/The White Swan: Natalie Portman

Lily/The Black Swan: Mila Kunis

Thomas Leroy/The Gentleman: Vincent Cassel

Erica Sayers/The Queen: Barbara Hershey

Beth Macintyre/The Dying Swan: Winona Ryder

Fox Searchlight presents a film directed by Darren Aronofsky. Written by Mark Heyman, Andrew Heinz and John McLaughlin. Running time: 108 minutes. Rated R (for strong sexual content, disturbing violent images, language and some drug use).

Monday, September 6, 2010

"Centurion" (2010)

Neil Marshall's "The Descent" was about a group of friends who lived to take risks, and were proud of them - yet they either never lived to tell their tales, or wouldn't dare speak of them after they had survived. Here is his latest, "Centurion", which is about the legendary Ninth Legion, a group of men who risked their lives in great peril every day, and again not much of anybody knew of the dangers they faced, nor the value of their lives.

When "Centurion" opens up, we meet Quintus Dias (Michael Fassbender). He's the sole survivor of some vicious raid by the Picts, the only group more savage and gruntingly brutish than his own legion. There is some introduction after the film's opening credits - complete with what's probably best known in epics as the "helicopter introductory nature shot" - whose job is to create the illusion that what's going on here involves some kind of high stakes. "AD 117. The Roman Empire stretches from Egypt to Spain, and East as far as the Black Sea". Already, the obligatory historical rundown that prefaces such a stripped down film feels out of place, trailer-ready to pander to a formula that had me wishing for more of Marshall’s unrelenting claustrophobic horror, rather than his pre-occupation with displacing it in ancient middle Earth.

Then again, there are two arguments for and against the historically prolific accessories known as "swords and sandals", and taking a pro or con stance ultimately will depend on what you value more: the part that's historical, or the part that's prolific. Return to a swords-and-sandals epic and you will find yourself in all too familiar territory:

One man - decidedly of militaristic importance and stature - lies in the center of clashes of violent dispute in ancient Rome, then finds himself torn apart by captivity, love triangles of messy sexual tension, and a moral quandary that could probably make dying on the battlefield a pleasing, more convenient alternative.

He also presumably holds his base of knowledge of the genre within the confines of those tired Roman soldier films - among them "Gladiator" and "300", - which some I imagine will find to be homage with an adept level of respect. What "Centurion" is, is an exercise in style that recycles what it perceives to be authentic, and that becomes sort of hit or miss.

To start, Neil Marshall approaches his mythology with the same kind of awe and curiosity a kid staying the night at a friend's house telling a local urban legend has. In that way, it's hard to resist. One great shot of the Legion in battle sees flaming boulders closing in from every which way, mirroring that smothering paranoid feeling Marshall managed to get from those caves in "The Descent".

Marshall clearly understands that what we can conjure up in the darkness of our imagination - whether that's a vicious throng of monsters at the bottom of an unexplored cave, or a troupe of Roman soldiers whose fate is swept of recorded documentation - is most compelling when placed in a fragment of reality; the journey of backpacking young women or the waging battles of the vast Roman empirical struggle. Where the film falls flat, is when that aura within the context of historical legend becomes essentially removed, replacing something so potentially rich in lore with highly stylized limb-hacking choreography. Translated into horror, that paranoid hysteria is most effective when unexplained, but in “Centurion” the action begs explanation.

The film's strictly black and white characters also have a curious way of glossing over anything reminiscent of real dimension. Many of them, including Roman-epic veteran Dominic West as General Titus Flavius Virilus (there’s a mouthful) act as pawns in some cruel game rather than human beings. Marshall no doubt relished in the opportunity to dress down, ugly up and make a brute out of Olga Kurylenko, here playing Etain, the merciless and deaf Pict warrior whose makeup looks plucked out of a missing Joel Schumacher “Batman” installment. We’re told at some point that her motive is vengeance on behalf of her murdered family. I had trouble seeing more than the anger and brooding called for in an almost entirely silent and wasted role.

What I found myself repeatingly asking was a matter of the great moments that could arise out of a story willing to report unwritten history. Was every Pict simply a ruthless sadist? Every Roman a man of honor and glory? Where are those Romans whom secretly despised the civilization that forced them to fight to fatten their emperor, instead of blindly obeying it? When will we see a movie about them? Or maybe with "Centurion" we have, we just haven't seen it illustrated in any way beyond ancient Roman, swear-injected fraternizing and the bonding through their bloodshed that’s become so commonplace in a marketplace dominated by the interests of the modern bro-dude’s Facebook page.

The film's Video-On-Demand offering - compatible with video game consoles Xbox 360 and Playstation 3 - illustrates pretty clearly the audience Marshall's film will be tapping into. Sure, some pumped up, avid gamers hooked on a role playing game like God of War would likely enjoy taking a break from their game-play to download it on their consoles and watch it re-enacted, and "Centurion" is a well made representation of its own cornered genre. It is lean, concise fare whose business is fetishizing brawny, overbearing male archetypes and their exploits, which mainly consist of pillaging, mutilation and total conquest. My question watching was, didn't we just get all that playing the game?

★★☆☆☆ (2.5/5)

Cast & Credits

Centurion Quintus Dias: Michael Fassbender

Commander Gratus: Andreas Wisniewski

Vortix: Dave Legendo

Aeron: Axelle Carolyn

General Titus Flavius Virilus: Dominic West

Etain: Olga Kurlenko

Magnet Releasing Presents a Film Written and Directed by Neil Marshall. Running time: 97 minutes. Rated R (For Sequences of Strong Bloody Violence, grisly images and language).

You can find this review, its supplemental materials, as well as other extensive film coverage at EInsiders.com.

Tuesday, August 24, 2010

"Piranha 3D" (2010)

"Piranha 3D" works and delivers on two effective levels that create an awesomely nutty communal movie-going experience, one that only be described as either gleefully over-the-top or some of the most hilarious deadpan humor in recent years, or both. Aja is making a conscious effort to evoke response with his blood-spattered ice cream sundae, and much fun is to be had amidst the vast array of "Holy Sh-t" moments the movie throws at high speed.

The film also understands the more novel origins of 3-D, and here it chooses to make unabashedly gratuitous use of its gimmicky gags, almost as if to poke fun at the fact that they're otherwise needless in the cinema altogether. One girl has one two many shots of tequila, so naturally we get 3D vomit off the side of a boat. An obligatory party guy douses us with the foam of a keg. The women are gorgeous, decadent and free-spirited so 3D full frontal - and rear - nudity is what we get. It's "Piranha 3D"'s boozy 80's horror/sex comedy allusions like these that are not only refreshing in the context of their usage, but also deepen my appreciation for the movie's ability to value the other films its modeling, rather than mock them with the tired pretense that it's just "so bad it's good".

"Piranha"'s rather apt and clever direction is more concerned with the vapid plights of its pitch perfect cast without relying too much on plot, which is kind of irresistible. There's Elizabeth Shue as Lake Victoria's rhinoceros-skinned local sheriff Julie Forester, and the great Ving Rhames as her equally badass deputy counterpart, Fallon. The "wild, wild" gratingly sleazy misogynist pornographer Derrick Jones (Jerry O'Connell) seems to be sending up - or paying homage, or doing a variation, take your pick - of the greater portion of O'Connells catalogue of roles as which works just right. Adam Scott as Novak and Christopher Lloyd as Mr. Goodman who rope in the essence of this slum-show, with the kind of hammy acting Mickey Rourke tried for in "The Expendables" with no supporting beams. Even Eli Roth steps in with gleefully silly lightness to emcee a wet t-shirt contest.

Steven R. McQueen is at the center of it all as Jake, and is absolutely lifeless on screen; the movie knows this most of all, and virtually mocks the idea of real acting in a movie about crazed cannibalistic fish invading spring break. Whether this is intentional to the credit of director Aja or simply happenstance I'm not exactly sure. One almost feels like Jake's wholesome obliviousness was plucked from someone like Lawrence Monoson's Gary from the 1982 cult film "The Last American Virgin", though with a slightly more slanted edge of amorality.

"Piranha 3D" places itself at a patient ease with its intoxicating B movie quietude, and does a pretty good job of maintaining a sense of calm before the blood bath ensues. For a stretch, the hordes of piranhas roaming the depths of Lake Victoria are obviously deadly, but relatively non-threatening; their predatory killing instinct is first revealed in slasher "one-by-one" convention, beginning with Richard Dreyfuss as a man who bears no name, though we understand it's Matt Hooper when he's seen drinking a bottle of Amity Beer.

Most importantly, "Piranha 3D" knows exactly what it is, and after we've gotten a taste of this town of caricatures - this movie goes for it.

The crowd of Spring-Breakers remains blissfully naive, hedonistic, and ignorant to their surroundings. I seriously doubt this was a post 9/11 socio-political commentary, but it very well could have been, sans wet t-shirts, horny co-eds and the incessant pumping of Benny Benassi mixes. Their hijinks shamelessly set the stage for one of the most fiendishly absurd gorefest massacres put on screen in recent years. Aja's use of obsessively detailed practical effects in collaboration with Gregory Nicotero and Howard Berger on the multiplying mortal wounds is admirably apt; the scene itself surpassed "Kill Bill Vol. 1"'s record for most gallons of fake blood used in a film, and it makes "Saving Private Ryan" look like "Dora The Explorer". While that may sound disrespectful and dismissive to the serious attention that World War II movie deserves, it's the same kind of attitude these hapless dimwits would have had toward anything solemn at all.

And so they die their horrible deaths, and we laugh in shock and awe.

★★★★☆ (4/5)

Cast & Credits

Richard Dreyfuss: Matt Hooper

Ving Rhames: Deputy Fallon

Elizabeth Shue: Julie Forester

Christopher Lloyd: Mr. Goodman

Eli Roth: Wet T-Shirt Host

Jerry O'Connell: Derrick Jones

Steven R. McQueen: Jake Forester

Jessica Szohr: Kelly

Kelly Brook: Danni

Riley Steele: Crystal

Adam Scott: Novak

Ricardo Chavira: Sam

Dina Meyer: Paula

Paul Scheer: Andrew

Brooklynn Proulx: Laura Forester

The Weinstein Company Presents a film directed by Alexandre Aja. Running time: 89 minutes. Rated R (Sequences of strong bloody horror violence and gore, graphic nudity, sexual content, language and some drug use).

Friday, July 23, 2010

"Life During Wartime" (2010)

There’s a lot of talk of the humanization - or lack there of – of the monsters that pervade the mainline of the outside world in “Life During Wartime”, the new film from director Todd Solondz. The director first made a name for himself by branding absolutely no subject too taboo to hold under his microscope of twisted humanity, gauging every topic from the overlooked sadism of middle-school adolescence in “Welcome to the Dollhouse” to the ambiguous, dark and sometimes hilarious corners of sexuality in “Happiness”. Both films maintain a certain level of mastery that solidifies credibility. Shot with an eerily humane blindness to objectivity accompanied by patient, steady pacing and razor-sharp wit, Solondz has uniquely pastiched portraits of socially distorted losers and misanthropes, whose richly dimensioned presense haunted us long after their journeys into perverse self-fulfillment. One does not go into a Todd Solondz film in the hopes of participating in some misty-eyed road to redemption.

His latest ranges from the usual dark, closeted suburban observations on everything from rape, pedophilia, suicide and murder, though on this particular outing, Mr. Solondz is scaling interests the director himself described as “a little more politically overt”. Here he places themes of forgiveness and emotional fortitude against the backdrop of a post-9/11 sense of paranoia that seems to have taken hold of the three sisters Trish (Allison Janney), Joy (Shirley Henderson) and Helen (Ally Sheedy), and the rest of their family, comprising a microcosm of neurosis and dysfunction.

A sound understanding of the color spectrum, from black to white, might be a basic operating principle that ought to be in place when dealing with themes of this magnitude. There is a strength of unpredictable fluidity from Solondz’s relationship with that color black - known commonly as the only shade with utter absence of color - and its adverse white, the collective blending of all colors, one that shocks, rattles, astounds and even caps off its defining moments with some troublesome humour. In this context, these colors would allude to the obsessive intricacies of their respective characters, like some depraved subjects of a pulp-filled cartoon. What made "Happiness" so swift in its movement was its observation of the ways one operates when in a state of sexually arrested development, and its horrifying revelation of how these people maintain superficial acceptance in a society fixated on certain accepted levels of so-called "normalcy". The result is often hilarious, but also fundamentally sad.

“Life During Wartime”, which presents itself more as a follow-up variation than a sequel to the 1998 masterpiece that is “Happiness”, knows no such bounds, and forgets that this blend of restless black void once served a purpose in compelling those who watched to embark down unsettling, yet fascinating corridors of empathy. Here, Solondz’s formula has been watered down to a tactic that is gapingly less effective: Just how much dysfunction can we follow, and how unnerved will it render us?

Our revisitation of the Jordan family brings us to their newly settled home in Miami, where the offbeat peculiarity of this closely-knit bunch now seems to exist as one big parody. Trish (originally played by Cynthia Stevenson) and Joy (played by Jane Adams in the 1998 film) have found themselves again in their usual trappings. Trish begins a courtship with Harvey (Michael Lerner), a man whose Jewish blood, professed connection to Israel and gentle sincerity give her comfort she feared she may have lost ago; "You're so...normal!", she says. Joy continues to be haunted by an old boyfriend Andy (Paul Reubens) who's long since committed suicide, but still can't seem to let go of his lingering resentment. If not emotionally, she at least seems to be weakened down here by starvation.

There is implication that their search for male companionship is some bi-product of the effect of their sour sexual and marital experiences. But most of that melancholy is feigned this time around, and exhausted nearly to death with the same stomach curdling blend of static communication that played so fresh in Solondz's original effort. In one bit of the film's opening dialogue, Trish has a frank and explicitly sexual conversation with her son Timmy (Dylan Riley Snyder, in an incredibly precocious portrayal), whose naive concern for the mysteries of life begin to ruminate with his Bar Mitzvah ceremony approaching. For an exchange intended to illicit humor, the nature of this such scene has an adverse effect on its humanistic commentary, and the result becomes a disappointing exercise for those who might have been quick to excite over something as stalely cynical as this mock-shock-gag expo, described as a worthy companion piece. While Solondz's eye for this kind of exchange in borderline repulsion was so keen in "Happiness", "Life During Wartime" has decided to recycle what cannot appropriately be transposed, as the film begins to objectify the crises of its decidedly ill-fated characters. It's a shame, since they are - after all - a lost bunch of people, so obviously struggling with a considerable amount of angst.

Then there's the men.

The male characters in "Happiness" haunted us with a resonance in their passive aggressive disconnection. Bill Maplewood, played originally by Dylan Baker in arguably one of the most noble and uncompromising performances of the last twenty years, certainly gets a transformative revamp here. Ciaran Hinds, now in the role as the psychiatrist pedophile who shattered the lives and stability of his family years earlier, starts on a path to reunite with his son Billy (Chris Marquette), who is now at college, and now suffering the ramifications of traumatic stress that his father so consciously and tragically embedded in him. The culmination of that journey, however, feels rather insensitive to the events that preceded it, and ends on a note that's actually a little offensive given its circumstance.

I acknowledge that "offensive" is a slippery description of a film that features a pedophile in one of its leading roles, and perhaps I've overextended my critique of a black comedy. Hinds does, as all the actors do here, give a fine performance. And this is a film about forgiveness, right? Still, what can't be shaken is the feeling that "Wartime" depends on the bizarre humane window of "Happiness" as a crutch while diminishing that effect, and the material simply can't support it. One pivotal encounter speaks for itself:

Hearing a knock on his college dorm room door, Billy answers the door to find his father standing there, waiting for him. After letting him in, they engage in a discussion in which Bill questions, extensively, his son's sexual nature. What follows - a disclosure that his son does not have rape fantasies as his father does - suddenly turns into a line of questioning as to whether or not Billy is gay, and the question's response ("No") is met with a smiling sigh of relief.

If he grew up a pedophiliac rapist like me, Bill seems to say, well I'd have someone to relate to. But at least he's not gay. *Pfhew*.

Solondz's ambitions to wrestle with themes of forgiveness are admirable, specifically the juxtaposition of intimate family dysfunction and trauma in a post 9/11 world. But the film lacks the nerve to handle these characters with the compassion that "Happiness" granted, the compassion they deserve. Instead, a boy without a father works towards false absolution. Should he be? If Timmy forgives a father he cannot respect, who isn't there, how can he possess the capacity to forget? Or does he (like the film he's stuck in) just give him a pass? Revisiting these characters becomes sickly, frustrating and, well, unforgiving.

★★☆☆☆ (2/5)

Cast & Credits

Joy Jordan: Shirley Henderson

Allen: Michael Kenneth Williams

Trish Jordan/Maplewood: Allison Janney

Harvey Wiener: Michael Lerner

Timmy Maplewood: Dylan Riley Snyder

Bill Maplewood: Ciaran Hinds

Andy: Paul Reubens

Mona Jordan: Renee Taylor

Jacqueline: Charlotte Rampling

Helen Jordan: Ally Sheedy

Mark Wiener: Rich Pecci

Wanda: Gaby Hoffman

Billy Maplewood: Chris Marquette

IFC Films presents a film written and directed by Todd Solondz. Running Time: 96 Minutes. MPAA Rating: No rating.

You can find this review, its supplemental materials, as well as other extensive film coverage at EInsiders.com.

Wednesday, July 21, 2010

"Inception" (2010)

|

| Leonardo DiCaprio and Ellen Page peer out onto the shore of the subconscious. Inception, 2010. |

To explain the plot of "Inception" is pointless. Such an exercise would be like trying to explain someone how to work a Rubick's Cube, rather than just allowing them to navigate it for themselves, discovering as they go. It is the film's composition, its design, and ultimately its apt ability to evoke response that is infinitely more important. Some may find it laughable. Others will be quick to dismiss its dialogue as shallow minded psycho-babble. Those in admiration will incessantly pluck through its questionable holes in continuity, obsessing over arguments for something more tangible, more lucid. The objections one may have can only stem from either love or hate. Such is the mark of filmmaking of a high order.

"Inception" is a deftly blended cocktail of noir and surrealism, pulled off with the conventions of an action thriller that gives dreams a life that is both metaphysical and rich in its enormity. One of the film's secrets is the way in which it avoids giving its guiding vessel, Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio)'s journey one particular purpose. The lengths Cobb will go to attain catharsis are the only inklings he has of a compass. The weight of his conviction is measured by bold and breathtaking physical feats, instead of hand-delivered motivation, or "plot points".

I have read some criticisms of Nolan's sculpting of this kind of literal dream-scape construct as a negative, and understand where one might find it too objective. I do not believe in literal confines within narrative as being equated with literal-mindedness, and found it to work for me. With ways in which Cobb describes the depths of dreams he and his team set out to raid, I am reminded of a recurring action sequence from the James Bond franchise - in which Bond scales the outside walls of buildings with a harness and bungee cord, with some delicate determination to infiltrate. In a sense, this is Nolan's own Bond movie, and Cobb is his super-agent.

Descending, then reascending projections of reality, the subconscious mind, paradoxical occurrences and dreams within dreams manage to keep us in the present of each moment that holds this balance at stake, and translate what could be lost in pseudo-philosophy into compelling adventure. The film invites us to play a game that raises fundamental questions of existentialist dread, while confronting them as the characters do, through classical staples of the great heist and crew-oriented films like 1969's "The Italian Job" or Spielberg's "Munich".

The pieces to such a game are elaborate, but not without necessity. There is an assembling of Cobb's team that calls into play several members, all with a crucial importance. Their assignment - to perform inception, the covert implantation of an idea in one's mind to pass it off as that person's own idea - becomes fluid with the introduction of associate Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), Eames (Tom Hardy), Yusuf (Dileep Rao), a chemist, and the newly recruited Ariadne (Ellen Page).

At first I found myself asking why Cobb remained explaining the nature of their dream navigation in such consistent fashion, almost ad nauseam. Then it occurred to me: he's rationalizing this world as he goes, perpetuating the process of this continuous, unraveling one man. Cobb's brooding over wife Mal (played with haunting grace by Marion Cotillard) intertwines an emotional output that furthers the growth of this obsession with each devastating circumstance that rifts in time. DiCaprio has solidified his status as our generation's leading man, while adding ink to the stamp he has now made for himself as a purveyor of films dealing with psychological turmoil. It's a mark he can bear proudly.

|

| Dom Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio) plunges into his inner depths. Inception, 2010. |

All actors bring incredible range and a subtle sense of discovery to their roles. The character of Ariadne is a fascinating complement to Cobb in a similar respect, with her role as "architect" in their grand scheme sharing this constant discovery with his fiendish self-exploration. The always fresh Cillian Murphy, as Fischer, a young corporate heir at a crossroads of identity is again inspired in his role. Fischer's final meeting with a father with whom he has always been at odds plucks at hues of sadness, shame and self-doubt, which is met by a triumph of discourse and humanity.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Arthur is another expertly played performance of straight-forwardness. At times, he evokes the supporting and balancing sincerity of Robert Duvall's consigliere Tom Hagan in "The Godfather". Levitt's performance is always quietly calculated, with subtle mediation. He provides Dom and all those roped into his anxiety-ridden roller coaster with a sense of gravity that allows them to recollect themselves, while setting the film's pacing at ease.

I'll run the risk of stealing the title from a song by Jason Mraz when I say that "Inception" commands the powers of its cast with the dynamo of volition.

I have not met Christopher Nolan, and I have yet to hear him speak extensively about "Inception", as it was, as always, my prerogative to maintain a clean slate before absorbing the film. I do feel, however, that I know something about him. I know he believes in this construct of dreams he has created, in the same way Machiavelli perceives the world to be able to be condensed in a blueprint of conduct and decisiveness. I know that he is a man who is unafraid - without hesitation - to make films that exercise his relentless affinity for self-discovery, however dark or unfulfilling it might be. With "Inception", I think he has reached some level of fulfillment.

The essence of Nolan's vision could have likely drawn inspiration from the surrealist, paradoxical art of M.C. Escher, those mirroring echoes of deep-seated torment. Wally Pfister, a collaborator with Nolan dating back ten years ago in 2000's "Memento" deserves an Oscar nomination for his piercing cinematography, which inspires awe on the shores of our most primal human fears and dreams, literally and figuratively. There is a virtuous motif of a spinning top Cobb keeps nearby that is perhaps the most meditative of all of the director's iconic staples, more so even than the twisted philosophy of the anarchic Joker in his "The Dark Knight". To follow its presence as you watch, is to succumb to a seduction that harnesses universal principle.

|

| M.C. Escher's Drawing Hands, 1948. |

"Inception" can be viewed as a thorough massaging of the senses and a cerebral fantasy, although Dom Cobb is completely unaware of the existence of such make-watch-easy labels, which enriches the performance leaps and bounds. Its special effects are never exploited, but brushed over the film's ideas and notions with the faith that they'll stick. They are astonishing not so much by way of flashy demonstration, but in the way they are transposed, fixated on and revealed. The misconception of the film as a sci-fi shoot 'em up picture is an unfortunate communication breakdown, with advertising campaigns at the center of responsibility.

Make no mistake: this is a film withheld by no boundaries or contrivances. It's for anyone with a sense of marvel, who still yearns to take flight on their own terms. And for those who continue to challenge what we should accept as we inhabit the world, as each day passes.

Nolan's script contains what he understands to be true, designs it in abstraction and holds it to that standard, sending it all the way home. The film will also prove that virtually none of my review can encapsulate experience, only project it. I bear in mind that it is July, but for now, he has crafted the most captivating achievement of 2010.

★★★★★ (5/5)

Cast & Credits

Cobb: Leonardo DiCaprio

Saito: Ken Watanabe

Arthur: Joseph Gordon-Levitt

Mal: Marion Cotillard

Ariande: Ellen Page

Eames: Tom Hardy

Robert Fischer, Jr.: Cillian Murphy

Browning: Tom Berenger

Miles: Michael Caine

Yusuf: Dileep Rao

Maurice Fischer: Pete Postlethwaite

Warner Brothers presents a film written and directed by Christopher Nolan. Running time: 148 minutes. MPAA rating: PG-13 (For sequences of violence and action throughout).

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

"Iron Man 2" (2010)

Tony Stark is not so much fighting the Herculean villains his success adversely attracts than he's fighting himself. "Iron Man 2", a sweeping spectacle displaying showboating by its hero of the free-roaming, liberated sort, certainly opens on this note and speaks to such an idea. This time, the eccentric, ingenious billionaire (played by Robert Downey, Jr.) is first seen leading his annual weapons extravaganza, the Stark Expo, in Flushing, New York. While the original's culmination involved Iron Man's identity being nationally revealed, this sequel would have Stark assuming that role with a more than subtle embrace. Stark's magnetic allure feels possessed with live spontaneity, each scene admiring the way he gloats in his achievements. In one statement he professes, "I have successfully privatized world peace". It's a roguish conviction that dumps heaps of superiority complex on both his competition and his skeptics.

Downey, Jr. expands on the vibrant personality that defines Tony Stark as an enigma delivered on a platter to be wholly digested in its silly, over-the-top megalomania. In "Iron Man 2", we follow Stark's endeavor - aided by the distant, clouded memory and salvaged brilliance of his father - that builds toward reconstructing the inner-workings of his experimentally ravaged inner-core (a self-made orb embedded in his chest). His battery is literally running low - and poisoning his blood, as overseen by a "Blood Toxicity Monitor" - causing him to begin to die slowly. Frequently are moments in which the actor seems to be unchaining the assets he brings to this role, allowing them to run blind and rampant as a means of challenging his still prolific, yet out-shined co-stars.

The fact that my review pays exceptionally brief attention to Gwenyth Paltrow in the role of Pepper Potts is maybe a testament to just how little the film's plot pays attention to her, her story line, or her functionality as the love interest of Tony Stark. Potts is a woman who is essentially dismissed. Meditating on her relevance in this supposed "lead" female role brings to mind an old 1950's board game cover of Battleship, which features a father and son playing the game merrily at their leisure, while wife and daughter admire with a smile, washing dishes. In this context, she sits back and watches Tony's skylarking, serving as a personal aid of sorts, then is appointed by Stark as CEO of his company. The film seems to suggest that a position like this might fill her time, and allow her to "go play" while Tony's off handling bigger and better things. She'll still always be there when Tony's ready for her, after a day of fighting crime far more momentous than the company he's apathetically left in her faltering hands.

Subservience epitomized in Pepper Potts. Iron Man 2, 2010.

The great Mickey Rourke's casting in the role of Ivan Vanko is a clever move of casting direction that brims with possibilities. Possibilities of weathered emotion. Of grisly intensity. Of unadulterated villainous prowess. Of real nerve. Yet these possibilities are left unfulfilled, and viewers seeking to engage might want to know why Vanko is so unreachable, so one-dimensional. Rourke showed us his uncanny ability to connect and relate with the sometimes dark, sometimes light and bittersweet corners of the human soul in 2009's "The Wrestler", but here he's caught between a Russian accent, some cutesy one-liners and an ill-explained revenge motive that could sooner be resolved by out-innovating Stark rather than killing him off. He certainly tries, serving as an engineer to the smarmy weapons dealer Justin Hammer, in a fine and funny performance by Sam Rockwell. But this is Iron Man's movie, so naturally, nothing comes of it.

Or is Rourke here simply because his name will fill seats? Oh yeah, that's right, that's what it is. One can imagine a meeting with the film's producers nodding in agreement of casting for exactly this reason.

Back to Iron Man. Shall I applaud Downey, Jr.? Well, I am, respectfully so. My being self-conscious about that applause lies in the fact that much like Stark's weapons expo, "Iron Man"'s sequel is less a film with purpose than an extravagant looking one-man showcase, with Mr. Downey at the helm of its charms. All others on screen seem undeservingly dwarfed. Their roles somehow get lost in the film's narrative, reducing a band of unmistakable talent and stature to life size cardboard cut-outs rather than fully developed characters. Less Comic-Con-esque references and more, you know, supportive acting, might have better served the mythology of attention worthy villains like Whiplash and Black Widow.

"Iron Man 2" shares the same narcissism its leading man totes so flamboyantly, with self-indulgent star studded cameos that wink at the camera as we stroll through its pre-packaged, well polished motions. Isn't that Garry Shandling? Scarlett Johansson is quick, savvy, and sexy as ever. Wow, Mickey Rourke is tattooed from head to toe - and he's doing a Russian accent! Of course there's Samuel L. Jackson, wearing an eyepatch no less, complete with his own entrance played in by soul-funk organs! Even Adam "DJ AM" Goldstein shows up as the bearer of tunes for Tony Stark's drunken company carousal. "Iron Man 2"'s tediously prolific and cast trigger-happiness is an element that works in only partial effect. On one hand it serves in creating a real world to comic book blend of storytelling that assembles an elitist fellowship characteristic of Stark's egocentric lifestyle. On the other it presents a series of Hollywood in-jokes and gags that rest on the shoulders of its big name actors simply being present. Which side of the coin works for you ultimately depends on how much you've decided to delve into the glamour and glitz of Tony's world.

That said world is sufficiently titillating, as any good super-hero action picture would present it, though its tangibility is a point of interest worth questioning.

Mulling over Iron Man's capabilities, I'm sure I must have missed the part in which he learns to freeze time. Stark and Lt. Colonel "Rhodey" Rhodes' (Don Cheadle) breezy conversational exchanges during those crucial split seconds as some highly lethal explosives are thrust in their general direction would certainly prove that feat. In keeping with one of the films repeated mantras - "Everything is achievable through technology" - perhaps "Iron Man 3" will have them brewing some mid-battle coffee inside Stark Enterprises' finest innovations.

In the vast Marvel comic-book universe of routinely disposable excrement, "Iron Man 2" delivers as a perfectly competent, efficient superhero movie. It moves at a swift pace and with deft electricity through its more candid and sometimes improvisational scenes touting its inimitable leading man. Its action sequences are as slick and well executed as one could hope, though they never amount to much more. Essentially, the film's mishandling of the franchise's original rebellious voice and mismanagement of its high-stacked cast make this second installment second-rate.

Rest on your laurels, "Iron Man 2" cynically suggests, on the laurels of your cast and its household names, on the laurels of your director's stylish sensibilities, and on the laurels of an audience's tendency to respond without too much care once summer rolls around. Filmmakers following that suggestion are sure to be successful in entertaining, as "Iron Man 2" surely is. My lingering fear is that they'll lose the ambition to transcend.

View this sequel as a careless diversion, and you'll enjoy it, but try to refrain from focusing on what it could have been. Maybe trying to forget the new testament for superhero films, Christopher Nolan's masterful "The Dark Knight", ever existed - at least for the brief time being - might help you a little in that regard. "Iron Man 2" isn't a bad superhero movie, it fits the bill. But its flaws and shortcomings only trigger a Pavlovian response in anticipation for Nolan's next Batman installment. In the meantime, this will do just fine.

★★☆☆☆ (2.5/5)

Cast & Credits

Tony Stark: Robert Downey, Jr.

Pepper Potts: Gwyneth Paltrow

Lt. Col. "Rhodey" Rhodes: Don Cheadle

Natalie Rushman/Natasha Romanoff: Scarlett Johansson

Justin Hammer: Sam Rockwell

Ivan Vanko: Mickey Rourke

Nick Fury: Samuel L. Jackson

Agent Coulson: Clark Gregg

Howard Stark: John Slattery

Senator Stern: Garry Shandling

Paramount presents a film directed by Jon Favreau. Screenplay by Justin Theroux, based on the Marvel comic by Stan Lee, Don Heck, Larry Lieber, & Jack Kirby. Running Time: 124 minutes. Rated PG-13 (For intense sci-fi action and violence, and some language).

Monday, May 3, 2010

The Science of Avatar: Talking Science-Fiction with Dr. Richard Kelley of NASA

With the release of James Cameron's Avatar on Blu-Ray in the past few weeks, I opted to revisit some of the film's most engaging aspects, this time in an angle somewhat unfamiliar to film audiences: the scientific and political bridge. Does Cameron's film propel past the surface of its extracted Aliens/Terminator/Titanic mash-up? Dr. Richard Kelley joined me in sharing many of these same connections and ideas.

Richard Kelley has worked in high-energy astrophysics since 1977. After receiving a BA from Rutgers University and a doctorate from MIT, he joined NASA at the Goddard Space Flight Center in 1983. He has worked on measuring the properties of binary X-ray pulsars, including the discovery of several new X-ray pulsars, and pioneered new sensors for high resolution X-ray spectroscopy. He has participated in several satellite X-ray observatories, and is currently working on a new orbiting telescope in partnership with Japan that will be used to study matter very close to black holes.

This is The Reel Deal interview:

MW: Which science fiction films made an impact on you growing up?

RK: War of the Worlds, 1953. The Time Machine, 1960. 2001, Star Wars and Empire Strikes Back.

War of the Worlds was great, and really scary to me as a kid. It seemed so plausible. Meteors landing in remote places of the earth, no place was safe. The way it ended was so clever. The Martians could not have known about microbes and our immune systems that have evolved to protect us. Once the Martians breathed our air, they were doomed. This might actually protect us if real aliens visit earth. Wells was an English teacher, but read a lot and had a great, logical imagination.

The War of the Worlds, 1953.

MW: Yeah, well that's happening again with Time Machine. Reinventing logic, manipulating it.

RK: I loved Time Machine because it really sparked my imagination. What could be better than moving through time to see history or the future? Our life spans are so short and I wanted to be able to move through time to get to what I was interested in seeing. I had even built my own small model of the machine in the movie!

The Time Machine, 1960.

Back to the Future actually did a good job of showing the irrationality of this – if you interact with events in a different time, you change the future, and perhaps even your own existence. The theme is wonderful to contemplate and H.G. Wells once again made it seem like it might work.

MW: What of Stanley Kubrick's film?

RK: 2001 for its special effects, and the way it portrayed that unusual way in which we might come in contact with extraterrestrial intelligence besides our own. All other movies were conveying aliens as monsters, and here's 2001, and it just had this huge black block. The long scenes of the astronauts living in space were fantastic for the time, they still hold up to this day. Then there's the fact that there was very little dialogue, I liked that. Modern movies feel this need to constantly fill the time with sound and action. Kubrick's film, you just heard a lot of breathing. You were really there as an observer on board. There was a relatable quality to space travel, you were on the ship with them. It also taught us that all software has bugs! HAL 9000 was a computer and only as good as its software.

2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968.

MW: There's that notion that a real-world education links to the creeping suggestion of what's on screen. Shouldn't commercial science fiction be held responsible for that, in a way?

RK: Yeah. I think Star Wars reached so many people because it inspired the imagination about life elsewhere in the universe, and for the images it created. Space ships were not all shiny and plastic as you usually saw, but used and dirty. The realism was there. This was a world in which you could easily move through enormous spaces, so the machines that did this were necessarily grungy and beat up. And then there were all of the creatures that inhabited the galaxy. So many oddball creatures that had their own languages. And this idea of an intergalactic saloon was so cool.

Star Wars, 1977.

MW: Was there a special interest, speaking from your perspective and background, in seeing a film as promising to deliver on the level of attention to detail as Avatar, through all its anticipation?

RK: My only real interests in seeing the movie was that it was a science fiction film and in 3D. I expected on some level that the CGI would be impressive given the power of modern computers and techniques, and that’s what I wanted to see. The storyline was OK. I didn’t really care about that as a priority and none of my scientist friends cared much about that either - though they are certainly enlightened and concerned people when it comes to indigenous rights.

MW: So just how authentic, how plausible are the film's science fiction elements? Are we looking at something more imagined and metaphysical or can this stuff actually kind of steer in the direction of some form of reality?

RK: First, on a technical level, I was overwhelmed by the visual panorama of the film. Seeing those space travelers coming out of their little “coffins” as they approached Pandora in that scene with that long, stretching spaceship interior, with people floating around as far as you could see, I thought - this is it. Everything’s changed now, this is the future of movie making. The attention to detail was extraordinary, none of it looked hokey. In later scenes, little things like insects flying around between you and the action, those subtle touches. And they got the physics right for the motion of vehicles, whether they were landing to flying through the air. Looking through that lens, as a physicist, that’s my test of a good space-based sci-fi movie.

One thing my colleagues and I went back to were those choppers. At first it struck me as really clever. I wondered why we don’t have helicopters that look like this - that is, two big fans that can each tilt forward and backward for high maneuverability. The only answer seems to be that they would have a lot of extra mass that you would have to lift, and this is not practical.

MW: Did they ever look good. Classic Cameron, extracting that grungy military iconography.

Helicopters in full assault. Avatar, 2009.

RK: Sure, they looked cool. And very realistic.

MW: That level of aesthetic realism can fool logic.

RK: The Na’vi looked kind of “right” too – tall (due to reduced gravity) and very lean and athletic, characteristic of creatures that live in the wild. They have to compete with other animals.

The avatars themselves were another creation worth coming back to. The idea of “mixing” DNA of humans and the Na’vi all seemed plausible. The way an Avatar would collapse to the ground if the human was disturbed was a realistic way of showing that the human was still in control of what the Avatar did. That leads back to the idea that the subconscious mind is actually a conscious one on a different level, which certainly many physiologists have thought about over the last hundred years, and seems realistic when you think that sometimes dreams really do influence our conscious state. So, I think the film’s fictional components are not that far off from what we humans can imagine might be possible some day.

RK: The big thing that never sat with me, though, is the ending. The big climactic finish had the tough, mega-macho marine type, Colonel Miles Quatrich, getting skewered by Neytiri. I don’t think he was the real bad guy – it was Selfridge, the corporate leader on Pandora. He was the one laying down the policy and rejecting all of the intelligence provided by the scientists for the sake of the unobtainium [, the mineral they're mining]. Quaritch’s job was to protect the mission. He was certainly cavalier about life and obviously didn’t care about the blue people running around in the woods and their sacred trees, but in a broad sense, he was just following orders. The company was the real villain there. In the end, we see Parker Selfridge merely standing in line to get on a space ship back to the dying planet he came from. It wasn't justified!

MILITARY.... Colonel Miles Quatrich (Stephen Lang)

OR

....CORPORATION? Who's the aggressor? Parker Selfridge (Giovanni Ribisi)

MW: You touched on human rights a little before. Much of the film is politically charged throughout. Then it particularly culminates in the third act of the film, with Jake ultimately choosing sides and inciting this violent confrontation alongside the Na'vi people - and an ethical commentary on the corporate mindset that dominates a lot of our global policies, with the humans' exploitation of the unobtanium found on Pandora. Does that kind of straightforward criticism of politics in the narrative resonate with someone as yourself, working for the American government?

RK: I had no issue with the theme of the film. Yes, in some sense I work for the same government that forcibly relocated and killed Native Americans, but a government is by the people that are alive at the time. Still, Avatar does raise a good question about survival of species. What happens if somebody else is sitting on something you want, for example oil? Are we ever justified in just taking it by force? What if we really want it and they have enough? And at what point does civil behavior, like trading for it, turn into all out aggression to obtain what you want?

MW: Would you say we're as out of touch as Selfridge and those aggressors, how we evaluate situations that may or may not benefit us to thrive as a society?

RK: The history of humans, and even other animals is that you take what you need. In the case of humans, we often first reduce those sitting on it to something that is evil and despised, like “savages” – this shows up in Avatar. In essence, that is what we have done.

Human-lead air raid burns down Hometree. Avatar, 2009.

MW: Just a bit cynical.

RK: We're only now beginning to see with some setbacks in the later half of the 20th century, that maybe we should think about doing something else that is less violent to survive. My guess is that there are still dark days ahead for humans as resources eventually get consumed the way they do.

MW: The film is anything but approving of government's involvement in scientific progress. There's a clear disdain and send-up of industrialism.

RK: Yeah, the industrialists and the military security forces there outnumbered the scientists.

MW: Is there a sense of friction felt among scientists today?

RK: I thought the relationship between the characters played by Weaver and the others was truthful. Both parties clearly didn't like each other, but had to rely on one another to pursue what they wanted, and this case, anthropology and biology vs. unobtanium. They tried to be civilized and maintain control as long as possible, but failed when the decision was made to remove the indigenous by force.

MW: That's something that's reflective of the collective attitude today, then, when those two collided?

RK: Films tend to exaggerate in order to tell it in the span of a couple of hours. My experience wouldn't tell me there is anything quite so dramatic as this in our present scientific and industrial world, with people actually shooting to kill to prevent something happening. Still, there is something like this happening in our own scientific world today – global warming. Industrialists, and certainly their conservative defenders in broadcast “journalism” fear controls and limits on their enterprises, so they label the scientists as liberals and socialists that are supposedly making this stuff up in order to impose socialism over capitalism.

MW: Much like the dismissal of Sigourney Weaver's character, Dr. Augustine. Her concerns get ridden off, basically as a form of hopeless, tree-hugging hippie propaganda.

The motley crew of indigenous studies. Avatar, 2009.

RK: Unfortunately they're becoming successful in describing global warming as something that you choose to believe in or not. It's a way to dismiss the scientific process that is really at the heart of the issue. Real scientists don’t actually care if there is global warming or not....Well, they might in a long-term sense for the viability of the planet, but not in terms of right and wrong. Science doesn't care who’s right. Scientists just want to observe the world and come up with testable measurements of their ideas about how things work. When a new idea or theory comes along to explain the data, that's when they move on and run with it as long as it works.

MW: Is this dystopian vision of the future something we're heading towards as a government, with our current attitudes about scientific ethics?

RK: I don’t think so, but I do certainly worry about the health of the planet globally. Democracy, unfortunately, seems to be a luxury of affluent societies. As things become more difficult for people, democratic idealism gives way to greed. Humans have not been able keep from using up their environment to the point where it is too late to fix it. This is seen in smaller settings, like island communities, which often survive now by tourism and not their own balance of nature. It’s hard for me to see the earth as all nice and healthy in a thousand years unless humans wipe themselves out and the planet reverts to total equilibrium. Looking back, this was again the theme of The Time Machine.

MW: Like Wells had a time machine himself.

RK: Extraordinarily clever, ahead of his time. That message is still relevant.

* The opinions expressed by Dr. Kelley are his own and do not reflect NASA policy.

Saturday, May 1, 2010

Tribeca Film Festival: 2010 (April 24th-May 2nd)

Upon my arrival at Tribeca on a hot, gleaming Friday morning at Village East Cinemas, I expected something of a plateau of a screening of the first film I set out to review, the Thomas Ikimi psycho-drama "Legacy". At this point, the grinding tensions of filmmakers in anticipation of the anointment of the 8th annual festival's top honors had now been lifted. Controversies and shock incited in such films as Michael Winterbottom's "The Killer Inside Me" and their presence for the remainder of the week might have been held in low priority, particularly after their initial storm of vehement defense of its violence in question by an objecting public generated by controversy not unfamiliar to the Lower Manhattan festival - or any festival for that matter.

Having already formulated this expectation, the unfolding of what ensued at that morning screening proved to be a juncture with pleasant surprise. 11:30 came and went as a packed theater anticipating the latest addition to rising star Idris Elba's steadily increasing catalogue remained seated in the illumination of dimmed lamps and shameless Delta airlines plugs (pre-movie trivia about the shooting location of "Lost In Translation" stretched into the airline's latest elite business class package to Tokyo, Japan!). Suddenly, that commercialism of a commonplace sort was replaced with far more engaging promotion, with the arrival of the film's writer-director Thomas Ikimi making an unexpected trip out to screen the film with his audience, as well as entertaining the questions that followed. Ikimi first apologized for his lateness, explaining "I slept rather late this morning. Just ran 12 blocks to get here". Such intimate revelations without pretension were largely characteristic of the festival for the duration of my attendance; there was a sense of informality that placed filmmakers, critics, and film lovers alike into a kind of ease and comfort that would make the experience enjoyable and comprehensive on a heightened level.

Even in my condensed and relatively short visit, the films among Tribeca's showcase proved worthy of celebration, despite the idiosyncrasies of ay one critic's reactions. During my final late night screening (found within the coverage that follows), I bear witness to both the awe-struck dropping of jaws and fixated, pensive gazes, just as much as the gasps, moans, even yawns - accompanied by an occasional walkout. The imprint commonplace with all the films I saw, good or bad, remained their ability to inspire strong reactions among its viewers. If this were the festival's only sole intention, its worth would be all but undervalued.

2010 Tribeca Film Festival Winners

Tribeca World Competition

The Founders Award for Best Narrative Feature – When We Leave (Die Fremde), directed and written by Feo Aladag. (Germany) – North American Premiere

Special Jury Mention: Loose Cannons (Mine Vaganti), directed by Ferzan Ozpetek, written by Ivan Cotroneo and Ferzan Ozpetek. (Italy) – North American Premiere

Best Documentary Feature – Monica & David, directed by Alexandra Codina (USA)

Special Jury Mention: Budrus directed by Julia Bacha. (USA, Palestine, Israel)

Best New Documentary Filmmaker – Clio Barnard for The Arbor (UK)

Best New Narrative Filmmaker – Kim Chapiron for Dog Pound, written by Kim Chapiron and Jeremie Delon. (France) – World Premiere

Best Actor in a Narrative Feature Film – Eric Elmosnino for his role in Gainsbourg, Je t’Aime…Moi Non Plus, directed and written by Joann Sfar

Best Actress in a Narrative Feature Film – Sibel Kekilli for her role in When We Leave (Die Fremde), directed and written by Feo Aladag

New York Competition

Best New York Narrative – Monogamy, directed by Dana Adam Shapiro, written by Dana Adam Shapiro and Evan M. Weiner (USA)

Special Jury Mention: Melissa Leo for her performance in The Space Between, directed and written by Travis Fine

Best New York Documentary – The Woodmans, directed by C. Scott Willis (USA, Italy, China)

Short Film Competition

Best Narrative Short – Father Christmas Doesn’t Come Here, directed by Bekhi Sibiya, written by Sibongile Nkosana, Bongi Ndaba (South Africa)

Special Jury Mention: The Crush, directed and written by Michael Creagh (Ireland)

Best Documentary Short – White Lines & The Fever: The Death of DJ Junebug, directed and written by Travis Senger (USA)

Special Jury Mention: Out of Infamy: Michi Nishiura Weglyn, directed and written by Nancy Kapitanoff, Sharon Yamato (USA)

Student Visionary Award – some boys don’t leave, directed by Maggie Kiley, written by Matthew Mullen, Maggie Kiley (USA)

Special Jury Mention: The Pool Party, directed and written by Sara Zandieh (Iran, USA)

Tribeca Film Festival Virtual

Best Feature Film: Spork, directed and written by J. B. Ghuman, Jr (USA)

Best Short Film: Delilah, Before, directed Melanie Schiele (Singapore)

You can find this review, its supplemental materials, as well as other extensive film coverage at EInsiders.com.

"Legacy" (2010)

The opening shots of director Thomas Ikimi's "Legacy" confront us with a terrific jolt, introducing its band of corrupted heroes through suspicion, disease, and finally gunplay in a setup for an action thriller with bold and fearless, if not misguided undertaking. This is a film that feels free to pace itself, to take its time and allow its story to unfold with a sense of purpose. It's a truly savory sequence with a design that dares to be great, assaulting viewers with a roughness that strokes the sensory receptors. The yarn of that breakdown of psychosis is unraveled by none other than The Wire's own Idris Elba. These shots brim with intensity, summoning a brooding atmosphere of doomy grit and realism. When it seeks to over-extend its reach to the dark sweep of a noir-ish blend of an everyman's version of a Frank Miller graphic novel, though, it's the same tacked on, self-serious tendencies of the better half part of this film's intriguing but messy stretch that does it in.

When it worked as taut character study, I found myself appreciating the depths the film choose to navigate, and Elba, as the weathered alcoholic black ops soldier Malcolm Gray, hits all the right notes. "Legacy" would not be my first screening of a true "actors' showcase" of sorts at Tribeca (later a still flawed, though more gripping piece like "The Killer Inside Me" would put forth an exercise on behalf of Casey Affleck in a similar vein).

One facet of Gray's jigsawed mind, the real (or imagined) relationship between he and his former girlfriend (Monique Gabriela Curnen) was fascinating. It's a glimpse into the window of ramifications and aftermath of a man who's chosen a violent and treacherous path, and the even more discomforting reality that he must choose to accept. This woman simply couldn't bear to function as an emotionally rigid, loyal companion, and turned in her darker times for someone to care for her. It's a reality that might just break the otherwise rock-hard, unflinching Malcolm. "Legacy" was intriguing in its portrait of masculinity and in demonstrating the grisly, haunting toll that murder, even when it comes with a profession or "mission" is still in nothing less than cold, cold blood. Through it all, Gray's fellow soldier and mentor, Ola Adenuga (Clarke Peters) tells him one thing: "Keep your head up".

Mr. Ikimi's fine and intelligently presented points begin to sag throughout too much of the film's middle stretch. Malcolm's fretting deconstruction hits an especially flat-lining low with its excessive and exhausting use of the "self-videotaping" technique that seems to be becoming somewhat of a go-to gimmick in movies, inserted whenever directors wish to show any characters in the midst of lonesome self-examination and scrutiny. The heavy portent that underlies here can't help but feel contrived. In this stretch "Legacy" is a kitschy mess that seeks to blend influences: part "Taxi Driver", part "Rear Window", part "Memento", and sadly, all boredom. At one point a man sitting to my right laughed involuntarily as Malcolm sat in front of his tripod nested camera, groaning "Today's a bad day". Does he know any other? Apparently these dark, sullen times and the demons we inhibit can only be coped with - not overcome - by a bottle of vodka and an utter contempt for life, though I guess I'd be insensitive if I suggested that Malcolm Gray cheer up and go for a run in the park.

Insofar as this heavy laden, down-trodden swamp of inner turmoil, Ikimi's ambitions seem to reach severely further than "Legacy"'s thrill-noir capabilities in a way that feels rushed; there's never any room for these ideas to breathe. The sweeping implications of Gray's politician brother's (Eamonn Walker) involvement beg us to follow through imagery and television broadcasts revisited obsessively throughout, though they never quite send home the suggestions of that legacy the title would entail. Any deeper meaning of the film's title gets lost in a plot that grows more convoluted with each of Malcolm's swigs of alcohol, and for a film titled "Legacy", the loss of that meaning proves to be a hefty compromise.

A Q & A with Ikimi followed the film's end credits, and in response to several questions he reflected on one review, to which he recalled, "Basically the reviewer said the only reason to go see the movie was Idris [Elba]'s performance". "The only people I will continue to make films for is my audience", he added. "You are what matters". Where that such critic spoke truths in his respect and his own right, maybe I wrung a bunch more out of the confusion of Ikimi's work. It wanders, but there is a head on the young director's shoulders. I hope he keeps right on making movies for his audience, and I look forward to his next.

★★☆☆☆ (2.5/5)

Cast & Credits

Malcolm Gray: Idris Elba

Darnell Gray, Jr.: Eamonn Walker

Diane Shaw: Lara Pulver

Valentina Gray: Monique Gabriela Curnen

Ola Adenuga: Clarke Peters

Scott O'Keefe: Richard Brake

Black Camel Films presents a film written and directed by Thomas Ikimi. Produced by Thomas Ikimi, Arabella Page Croft, Kieran Parker. Running time: 92 Minutes. No MPAA rating.

You can find this review, its supplemental materials, as well as other extensive film coverage at EInsiders.com.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)